A hidden labourer at the Zoo: Hamet Safi Cannana

By Dan Phillips, ZSL Library Visiting Scholar

On 25th May 1850, Obaysch the hippopotamus arrived at London Zoo. It was the first time a hippopotamus had reached Europe since antiquity and, like Jumbo the elephant after him, Obaysch the hippopotamus became one of the most celebrated animals exhibited in London Zoo during the nineteenth century.

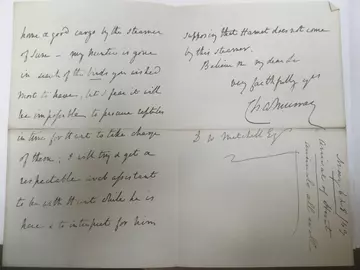

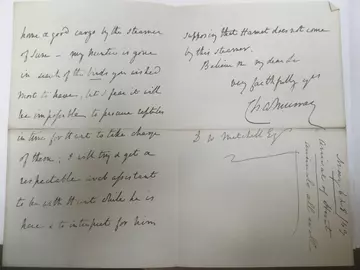

The story of Obaysch is relatively well-known, and even today his presence continues to enlighten researchers who visit the ZSL’s Library, where a small sculpture of him can be found. Yet when Obaysch first arrived in England, he was not alone. Metaphorically hidden behind what the newspapers dubbed ‘HRH - His Rolling Hulk’ was a man who accompanied this animal from Egypt to England and spent two years caring for Obaysch as he adjusted to life at the Zoo. The gentleman’s name was Hamet Safi Cannana. Very little is known about Hamet prior to the arrival of at London Zoo, but scouring through handwritten letters in the ZSL archive, it is possible to uncover a little bit about him. Hamet Safi Cannana was an Egyptian animal handler who had worked with Charles Murray (Britain’s consul-general in Egypt) for a number of years, and was well-known for his expertise in managing wild animals. Importantly, Hamet’s name first appeared in a letter from Murray to the ZSL Secretary David Mitchell in 1849, regarding a shipment of animals several months before Obaysch was acquired. If the shipment was to go ahead, Murray wrote, he would have to find another respectable assistant to translate for Henry Hunt (the Society’s head keeper) if Hamet did not return from his assignment in London.

Hamet is only mentioned in passing, but it implies that he had already travelled to England in 1849 and that upon returning to Egypt, he would try to accompany the second collection as well. Interestingly, the letter reveals that Hamet was bilingual, or at least satisfactorily fluent, acting as a translator for Hunt who was despatched to Cairo for the second collection. Although this is just a snippet of information, it may explain why Hamet was recommended as Obaysch’s primary handler as he was clearly very skilled. Either way, at some point before Obaysch arrived in Cairo in November 1849, Hamet returned to Egypt and quickly found himself attached to ‘the warm affections of Obaysch’.

Housed in the consult-general’s courtyard in Cario, Hamet cared for Obaysch throughout the winter months of 1849/50 whilst arrangements were made for the hippopotamus’ departure to England. Hamet was heavily involved in the process, and once Obaysch was placed on the steamship Ripon in May 1850, Hamet became his lead keeper. Hamet even slept in a hammock adjacent to Obaysch’s 400-gallon custom-built water tank, extending ‘one arm over the side so as to reassure’ his charge. Unfortunately for Hamet, he was regularly woken up by the sensation of a jerk and a hoist by his compagnon du voyage, who, if left unaccompanied, would run ‘through octaves of cries from the most plaintive to the most violent’. Obaysch was clearly quite attached to Hamet.

The steamship arrived at Southampton on 25th May, where a train was waiting to collect the hippopotamus. The train stopped at nearly every station, drawing large crowds who eagerly awaited to see the Obaysch. However, owing to the style of train carriage onlookers only caught a glimpse of Hamet who, for want of air, was constrained to put his head through the roof! It may not have been the most elegant journey, but they eventually arrived at the gardens. Once inside, Hamet was able to coax Obaysch into his enclosure with a bag of dates and like previous excursions to London, Hamet had once again succeeded in transporting an animal to the Zoo.

Hamet worked at the Zoo for the next two years, although it is not entirely clear what he did during this time beyond tending to Obaysch. Nevertheless, 1851 was the year of the Great Exhibition, making Obaysch centre-stage to approximately 667,243 visitors – almost double the average number of admissions to the gardens. It was a busy time to be his keeper. Hamet was also a translator for Jabar Abou Maijab and Mohammed Adu Nescian, two snake charmers who attended the Zoo in 1850 who were often quizzed by visitors – including Queen Victoria – after their performances. Hamet's service at the Zoo continued until December 1852, when he returned to Egypt, receiving £68 for his services.

This marked the end of Hamet’s time at the Zoo, but it did not take long for his name to reappear. In 1854 Hamet’s name cropped up again, this time regarding a second hippopotamus intended for the Zoo. Reminiscent of Charles Murray’s letters, the new British consul explained that Hamet had not returned from an expedition in the Sudan and could not accompany the female hippopotamus to London. Instead, Mohammed Adu Nescian (the snake charmer from 1850) was asked to take his place. Thus, in a pleasant turn of events and like Hamet before him, Mohammed ensured ‘Adhela’ arrived safely, enabling the hippopotamus pair to raise a baby hippo that lived until 1908.

Although there is still plenty to do be done regarding the history of ‘hidden labourers’, it is clear that Hamet was a prominent figure at London Zoo during the mid-nineteenth century. Despite the limits of historical sources, the case of Hamet Safi Cannana is an insightful example of non-European keepers working at ZSL. Indeed, by recounting the events of Obaysch’s first few years at London Zoo, it is possible to see what role Hamet played in this historic event. Thus embedded within Obaysch’s popular narrative, Hamet was present throughout, forming an essential role in the transportation and initial display of Obaysch the hippopotamus. In this way, Hamet’s story can live on through the animal he cared for and accompanied to England.

Dan Phillips researched ZSL's hidden histories for his PhD at Exeter University

Explore our Archive Catalogue