Emma Milnes

Deputy Librarian

This March, we will be celebrating the 500th birthday of the Swiss naturalist (born 26 March 1516), Konrad Gessner (or Conrad Gesner), and his key role in the beginnings of modern zoology.

As 3rd March is World Book Day, Gessner’s book is particularly appropriate to highlight as he attempted to describe all the known animals (and some unknown) of the world.

Gessner's background

Gessner was born in Zurich in 1516 to the furrier Ursus Gessner and his wife Agnes Frick. We do not know a great deal about Gessner’s family life, but it is believed that he was born in to a large family, where with so many mouths to feed, the young Gessner was sent to spend his childhood in the care of a grand uncle. It was with this uncle that Gessner’s keen interest in natural history began.

At an early age Gessner displayed an aptitude for linguistics and classics, and combined with his inclination for natural history, he deeply impressed his tutors of the time. So much so, that he was awarded a scholarship to study in Bourges University in France, in 1533. He later went on to teach Greek in Lausanne, and then Aristotelian philosophy back in his hometown of Zurich, where he then spent much of the remainder of his life.

In 1545, Gessner published his book The Universal Bibliography, in which he sought to record all of the titles of books that had ever been written since antiquity. Although the book took Gessner just four years to complete, it was a major accomplishment, and was widely praised for its comprehensive coverage. It was because of this book that Gessner earned the nick name ‘The Father of Bibliography’.

Historiae animalium

But, undoubtedly it is Gessner’s Historiae animalium (History of Animals) that is considered his magnum opus. Gessner’s work aimed to describe all of the animals that were known at the time, even though he would not have seen the majority of them in the flesh. Historiae animalium was published in four volumes between 1551-1558, with a fifth volume published posthumously in 1587. The first two volumes describe mammals, the third birds, the fourth aquatic mammals, and the posthumous fifth concerns serpents.

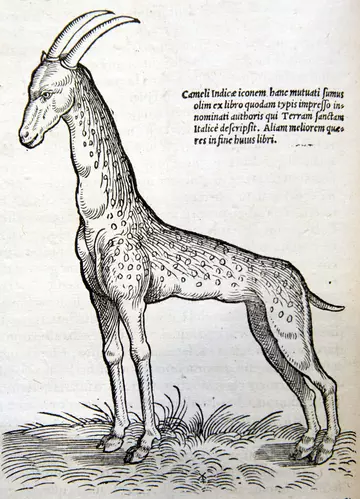

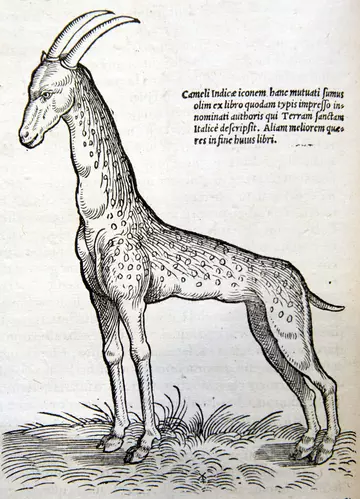

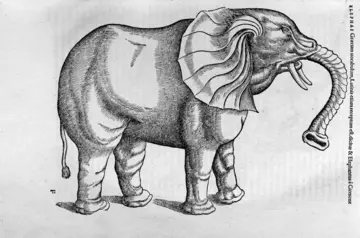

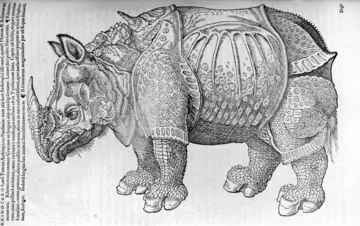

Gessner called upon the literature of early naturalists such as Pliny and Aristotle for many descriptions, and significantly he tried to gather as much physical evidence as he could by using traveller’s descriptions and specimens. Gessner amassed such a collection of zoological specimens he created a museum in house for them (rumour has it that this is where Gessner requested to be laid just before died). Yet despite Gessner’s best efforts for accuracy, there are still some ‘interesting’ descriptions and illustrations of animals, including an unusual looking giraffe, a unicorn and even a hydra! The images on this page are all taken from these books, but many more curious examples of animals can be found in the volumes.

Arguably, the most impressive aspect of Gessner’s Historiae animalium is the attention to detail with which he describes each species. Each animal has a woodcut to illustrate it, with a thorough description broken down in to eight topics. These topics included, among others, all the known names of the animal in living and dead languages, the animal’s physical description, geographical range, uses in medicine, and even any mentions in history and literature. Before Gessner, descriptions of animals were mostly in list format with only the more interesting, or useful, animals being given more thorough treatment.

ZSL Library holds 4 of the 5 original Gessner volumes of Historiae animalium, plus a later abridged version from 1560. These are some of the oldest volumes in ZSL Library. If you would like to consult any of these works in person, please contact the Library to make an appointment as they form part of our ‘special collections’.