ZSL

Zoological Society of London

This is a joint blog between us here in the ZSL Archives, and the Natural Sciences department of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (AC-NMW) in Cardiff, making links between animal specimens that moved (after death) from our collection in ZSL to theirs. We hope that this blog will give an insight into the rich connection between such collection. 6

Sarah Broadhurst, ZSL Archivist

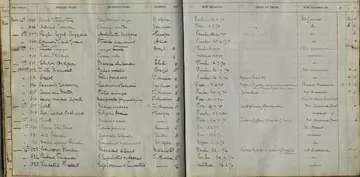

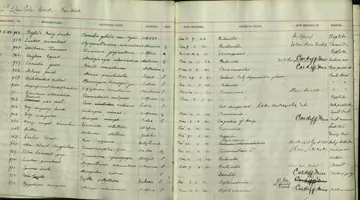

The ZSL archive holds a wealth of historical animal information. Some of our most interesting – but underused – items are a series called ‘Registers of Death in the Menagerie’ or more colloquially the ‘Death Books’. These run from roughly 1870, and are a fascinating record noting dates of birth and death, cause of death and how the bodies were disposed of. Below is an image from the very first register from 1870.

It’s really interesting to see the myriad list of conditions animals died of more than 100 years ago – some things which were common at the time such as tuberculous, or a ‘fatty liver’ are not common now, due to animal husbandry and our understanding of the dietary and lifestyle needs of animals having advanced so far. One of the most unusual I came across has been an Ostrich from 1900 who was found to have its stomach “loaded with raw meat and onions”.

Equally, it’s fascinating to see what happened to the bodies of the animals after they died. Some would have specific organs kept for study, some skeletons, and a lot of them went to external people and organisations. People such as Edward Gerrard, who was a famous taxidermist in the 19th Century, and Lord Rothschild, whose collection formed the basis of NHM Tring. You can see in the register page from below, the skin of a Grand Electus (a sort of parrot found in New Guinea and other nearby islands) was sent to Lord Rothschild.

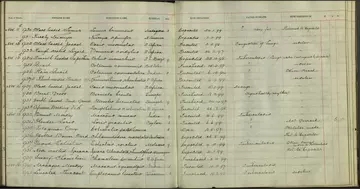

In the volume for 1922 (see below for an example page). I was really interested to see that a lot of specimens went to Cardiff Museum – so I got in touch with them to see if they had a record of what happened to these specimens after they came to them.

Jennifer Gallichan, Curator Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (AC-NMW)

Over the years, museums have played an important role in taking on these animals and there has been a long history of donations to museums from zoos.

I work as a curator in the Natural Sciences department of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (AC-NMW) in Cardiff. Our vertebrate collection has its origins in the Cardiff City Museum; we still have about 200 of these specimens, mainly mounted birds and skeletal specimens, the earliest dating back to 1882. It has grown since then but is still relatively small holding approximately 12,000 cabinet skins, 8,000 glass negatives, 7,500 clutches of bird eggs, 4,000 skeletal preparations and 1,800 mounted specimens.

I was contacted by Sarah, the archivist at ZSL who was tracing records of specimens that were donated to AC-NMW in the 1920s. Our accession records revealed that the amount and range of specimens donated were significant, and that this relationship lasted for decades. We have records of donations between 1921 and 1979, with a total of 83 specimens coming to the museum from the zoo.

It is a tantalising list of the exotic. Animals from far-flung places like the Australian Water Dragon, Egyptian Mongoose, Bengal Monitor and Javan Mouse Deer. Also the unusual, a Coypu, the Greater Malay Chevrotain, a Western Swamphen, and my favourite, the Red-faced Lovebird. All would have been significant contributions to the national collection which at that time was growing. So what happened to these specimens? Are they still in the collections?

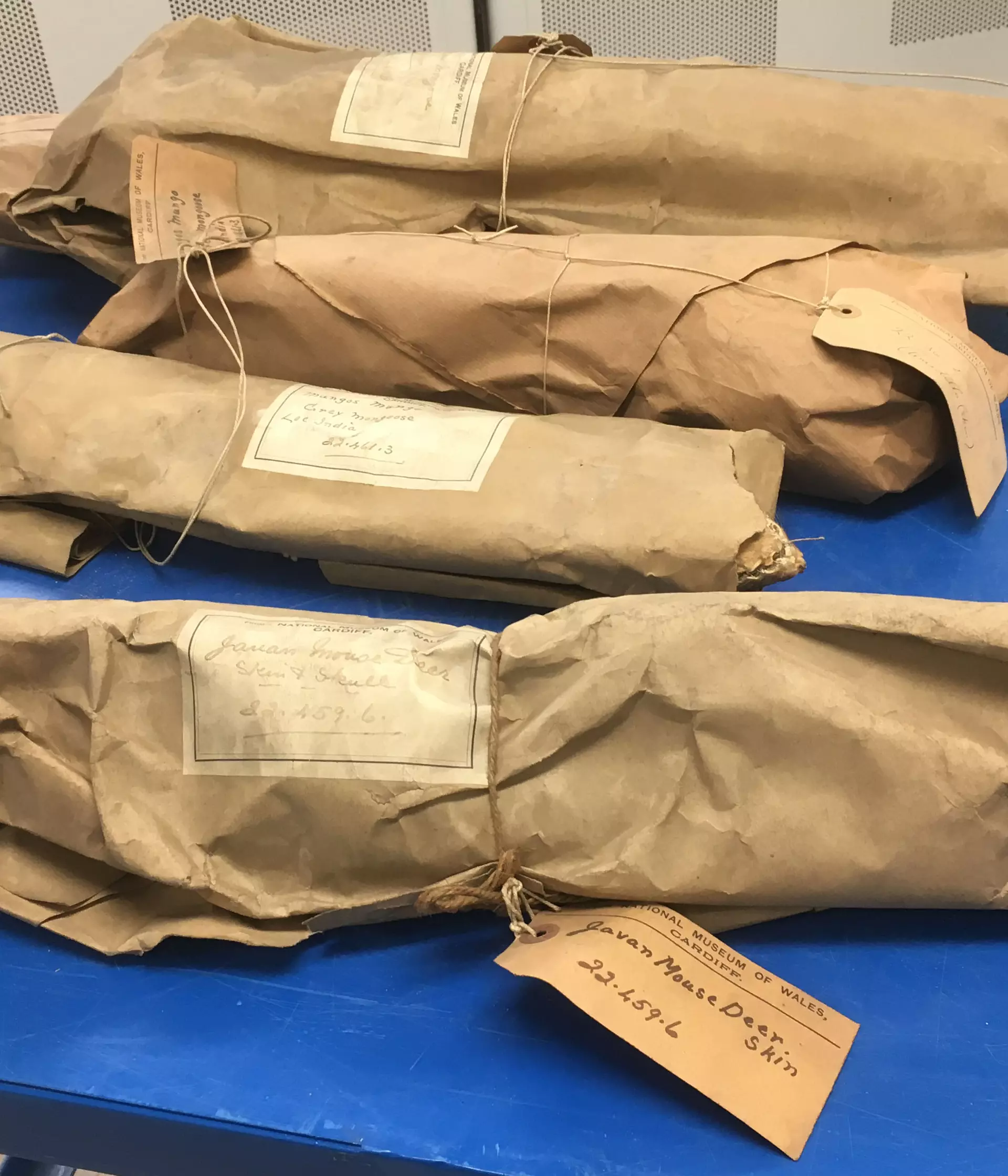

We focused on just the donations from 1922 to 1923, as this was a bumper year with donations of 49 animals. Almost all of the specimens are still in the collections nearly a hundred years after they first arrived here. The majority of them are stored as cabinet skins, some with the skull still attached. Interestingly many of the specimens had locality data with them indicating that they were collected from the wild. This differs significantly from modern zoo animals that are captive bred rather wild caught.

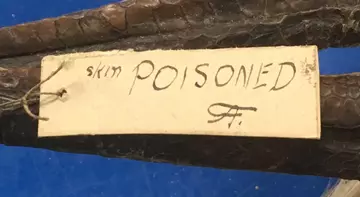

Unusually, a large proportion of the material was still in its old brown paper packaging, despite this they all seemed in good condition. It is unclear how the animals have been preserved, a couple of specimens bear labels stating ‘skin poisoned’, most likely referring to the application of chemicals, such as arsenic, which have been applied to the skins to protect them from bio-deterioration and pest infestation. Many of these chemicals are harmful, so unpacking, cleaning and re-housing these specimens will be an interesting project for next year.

So what do museums use dead animals from zoos for?

One of the primary roles is in education and promoting the public understanding of science. This could be through focused workshops with schools or outreach events with our visitors. We use the specimens to talk about a whole range of subjects such as evolution, adaptation, diet, reproduction, camouflage, food chains, and much more. They are also really important in scientific study, aiding researchers looking at anatomy, sampling DNA, even bioengineering. Many species tell important conservation stories about the state of the planet’s declining wildlife and what we can do to protect it. A recent acquisition of a Sumatran Tiger from The Welsh Mountain Zoo in Colwyn Bay was used to raise awareness of the plight of tigers in the wild.

Lastly and probably most importantly, they become important reference specimens cataloguing wildlife on Earth for generations to come. Many extinct species are now only found in museum collections such as specimens of the Dodo, the Great Auk and the Tasmanian Wolf. Who knows what other species will only be found in museum collections in the future?

You can learn more about the fascinating collections of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales (AC-NMW) at https://museum.wales/collections/, and you can follow Jen's department of Natural Sciences on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/CardiffCurator.